The whaling industry embarked on an era of unprecedented growth in the 1760s, and though American whalers continued to hunt bowhead and right whales, as well as gray and humpback whales, they directed most of their resources at the sperm whale, which could be found in most of the world’s oceans, migrating toward the equator in winter and toward the poles in spring. Once again, Nantucketers led the way, having added the species to their list of prey decades prior, in the days of shore whaling; unlike other whales, sperm whale carcasses floated, making it easier to tow them ashore. But the species’ other unique and profitable characteristics made it the industry’s primary target once shore whaling gave way to pelagic whaling.

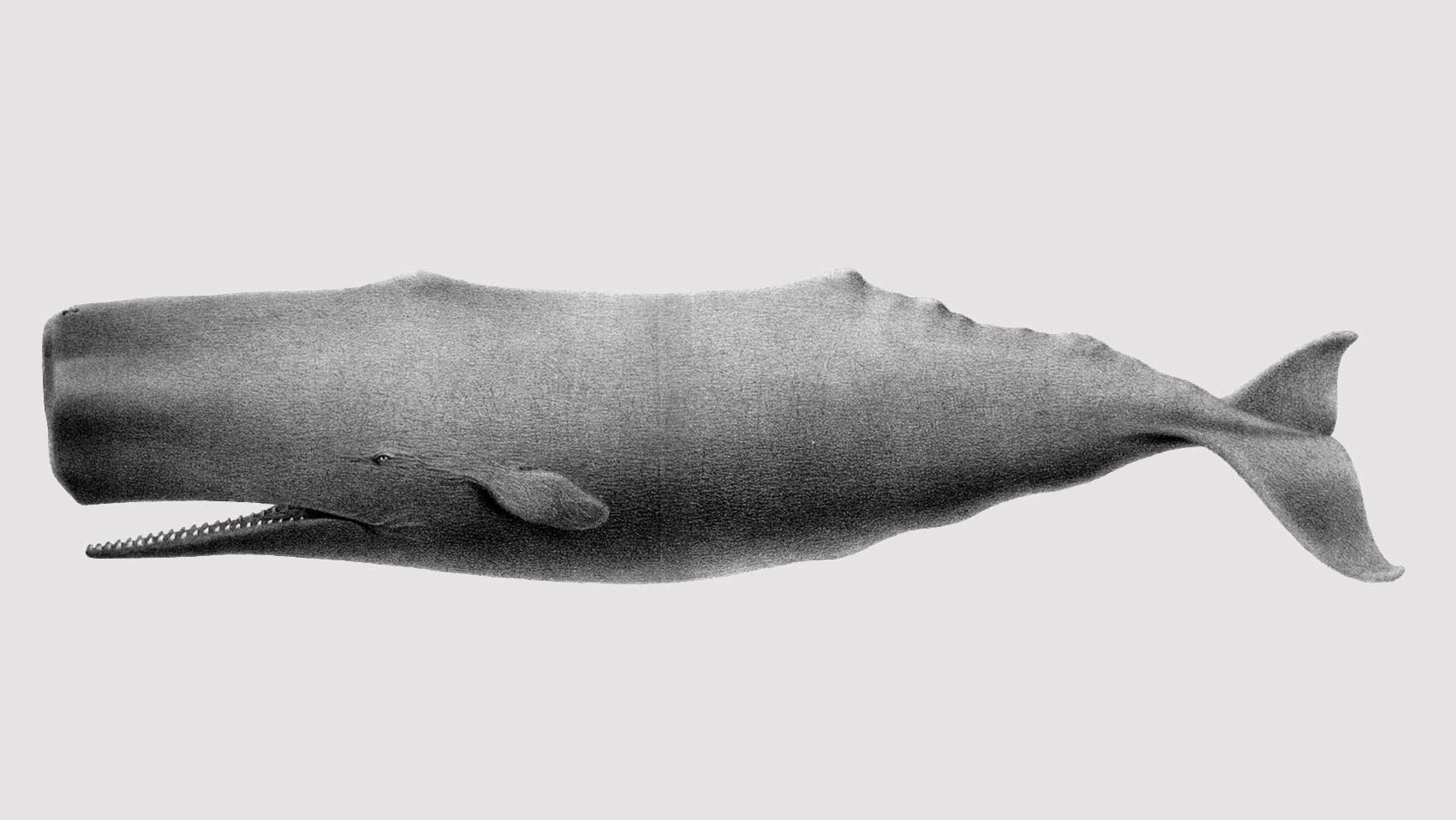

Male sperm whales average fifty feet in length and weigh about forty tons, but they can reach sixty feet and weigh as much as sixty tons; females average thirty-six feet and weigh about twenty tons. The sperm whale has the largest head and brain of any animal (accounting for about a third of the whale’s length), and the largest tail, in proportion to its body, of all whales. It dives deeper—sometimes more than a mile—and can remain submerged longer—upwards of an hour—than any other whale.

The sperm whale was faster, more powerful and more aggressive, and swam in deeper and more distant waters, making it difficult and dangerous to hunt. And, being an odontocyte, or toothed whale, it did not provide the much sought-after commodity of baleen. But it had other qualities that made it highly desirable prey. The oil derived from its blubber was finer than that produced by other species, yielding lamp oil that burned cleaner and brighter. And, on occasion, it produced ambergris, a dark, waxy, and very rare substance caused by irritation in the stomach or bowels. Ambergris had been prized by various civilizations for more than a thousand years. The Egyptians used it as incense; the Chinese as an aphrodisiac; Italians added it to chocolate; Arabs added it to coffee; and the English used it as an ingredient in cake frosting. But in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries ambergris was valued most as a fixative that helped perfumes retain their scent.

The whale’s greatest/most valuable prize, however, was a clear liquid housed in a large cavity in the front of its head. Called spermaceti for its tendency to turn milky white upon contact with air, its function remains unknown. One theory is that spermaceti and the cavity that contains it together act as a cushion when the whale uses its head as a battering ram in battle with other whales (or, on rare occasions, with whaling ships). Other theories are that it somehow aids in echolocation and communication with other whales, or that it controls buoyancy, helping the whale to dive to great depths or rise to the surface. Spermaceti’s purpose may be a mystery but the whaling industry found uses for it: in addition to being used for medical purposes, and sold as a cream or lotion, spermaceti was used to make the finest, most expensive candles on the market. Spermaceti candles produced little soot; they burned cleaner and brighter than any other kind of candle and became a luxury item for which the well-to-do were willing to pay a premium.

The sperm whale would remain the industry’s big moneymaker for nearly one hundred and fifty years, throughout the nineteenth century and into the industry’s final days in the 1930s. It also captured the public imagination, giving rise to Moby-Dick and many other representations in art, literature, and nonfiction accounts published in books and newspapers.

__________

Sources

- Leviathan: Our History of Whaling in America, Eric Jay Dolin,W.W. Norton & Company, New York, NY, 2007.

- Moby-Dick, Herman Melville, 1851.

- In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, Nathaniel Philbrick, Penguin, New York, NY, 2000.

- And Yet They Come: Portuguese Immigrations from the Azores to the United States, Jerry R. Williams, Center for Migration Studies, New York, 1982.