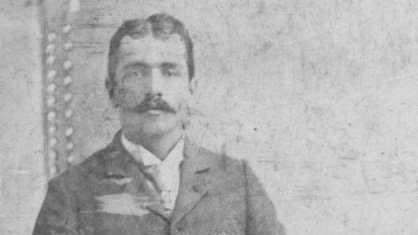

The story of the Freitas family in America begins with Frank Freitas I, the Azorean immigrant who arrived in New England in the 1860s. (To distinguish between this Frank Freitas and the three who came after him, we’ll identify them as Frank I, Frank II, etc.)

Frank’s story might seem unusual — a poor, uneducated man from a tiny island in the Atlantic makes his way to America, and then all the way across it in the post-Civil War era — but as we’ll see in the chapters ahead, his story is fairly typical of Azorean men of the mid-nineteenth century. Less is known about his wife, Mary Swazey, who was also from the Azores, but tracing Frank’s life may give us some insight into her, too, as her father’s immigration experience may have been similar to Frank’s.

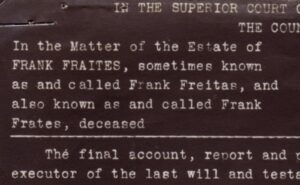

There are many difficulties in researching Frank Freitas, and the first stems from the fact that his surname has many variations. The correct Portuguese spelling is Freitas, or de Freitas. Portuguese surnames often include particles like e (“and”) and de, da, do, and dos (“of” or “from”). The particle is not technically part of the surname; in Portugal de Freitas would be alphabetized under f, not d. But in America, the particle would either be dropped entirely or would become officially part of the name, sometimes earning a capital D, sometimes pushed together with the name to form new variations: De Freitas, deFreitas, DeFreitas, Defreitas. Add to those variations all the possible spellings — Fraites, Frates, Fratus, Fratis, Fratas, Fretis, and others — and there are dozens of possible versions.

Once Frank settled in the United States, we know that he used at least three spellings: Freitas, Frates, and Fraites. In fact, the decree settling his accounts after his death uses all three versions every time his name is mentioned. Frates appears to have been the spelling he used most frequently, at least during his years in California. His last will and testament, however, uses Fraites as the primary spelling. And the original Portuguese Freitas is what he had inscribed in 1911 on Mary’s gravestone, where he would later be buried beside her. So we might consider that the final word.

Another difficulty in tracing Frank I is that the name Frank Freitas, in any of its spellings, is a common one among Portuguese immigrants to the United States. Census data show many men with that name in California and in the Bay Area, and the name frequently appears in other documents about Azoreans and the Portuguese in America — voter lists, ship passenger lists, etc. Many of these men had similar life trajectories, migrating to the same places and adopting the same occupations.

Frank’s true surname contained the particle de — Flora Freitas Dowdall once confirmed that the original spelling of the name was de Freitas — but the name was simplified and the spelling changed either upon arrival in the United States or while in transit.

But Frank’s surname was not the only one to undergo a transformation; his first and middle names also were changed after leaving the Azores. Frank is the anglicized version of Francisco, and Antone is an anglicized version of António. Thus the man who lived most of his life as Frank Antone Frates was likely born with the name Francisco António de Freitas. Again, this poses a problem, for Francisco de Freitas and Francisco António de Freitas are very common names in the Azores, then and now. In fact, almost all Azorean names are common: most of the surnames found on the islands are traditional Portuguese names, and until fairly recently, Azoreans rarely chose anything but traditional first names for their children, usually naming them for Catholic saints; to do otherwise would be considered frivolous and would risk embarrassing the child.

Ascertaining Frank’s birth date is a relatively small problem. While there are a few documents that point to 1847 as his birth year, most information points to 1841. Census data is fairly consistent on that point over the course of his life, and one census lists his date of birth more specifically as August 1841, which fits well with other information about him — that he was considerably older than Mary, that he was 70 when he made out his will in April 1912, and that he was in his early 90s when he died in 1934. The difference between 1841 and 1847 may seem minor, but it becomes significant in determining when and why Frank left the Azores and what his emigration experience may have been like.

Tracing the life of Frank Freitas I is not easily done, because of the issues above and because few details of his life were passed down. But a glimpse of his life story can be patched together from brief remembrances of him by a few of his children and grandchildren. And by placing those details within the larger context of Azorean and American history during the nineteenth century, we can form a general account of Frank Freitas and Mary Swazey’s life together, and how these two people from a small, remote island in the Atlantic crossed an ocean and a continent and wound up in what is now the small, semi-remote, and seemingly abandoned town of Port Costa, California — population 300.